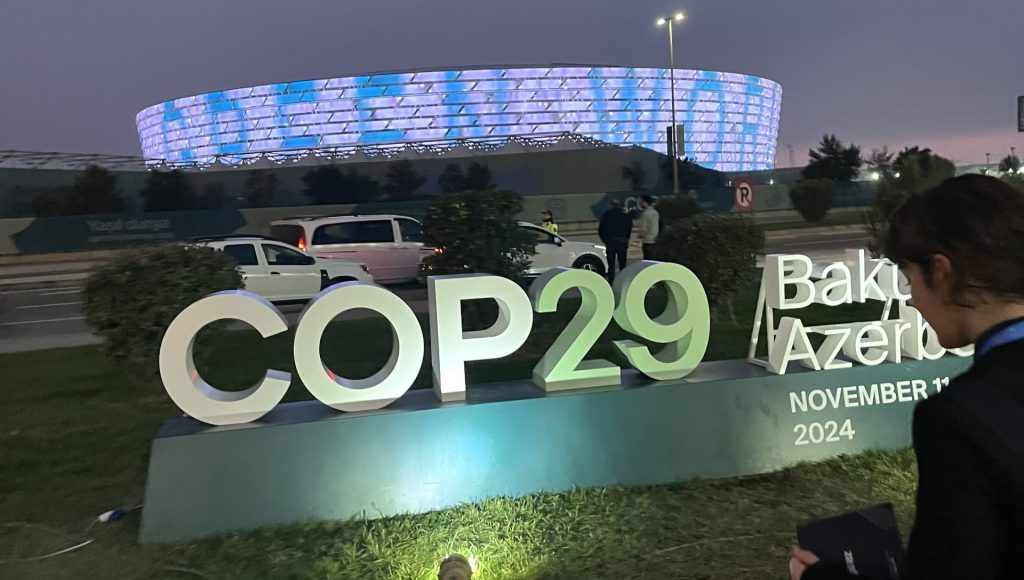

Report and photos: Filip Blagojević, youth delegate of RES Foundation in Baku

Limited progress or just progress?

Can progress be qualified – it was one of the questions and the backbone of the discussion at one of the negotiations. Specifically, at the negotiations related to National Adaptation Plans (to climate change). Do the negotiations really go to those details, apparently banal, and negotiations between all the countries of the world…

Yes, they do!

It may seem superfluous for such a place, but it is definitely necessary. It’s nice that at those negotiations, in the same volume, you go from discussing an “important” topic (for example – how much money developed countries will give to less developed ones) to some “banal” topic about whether the comma should be followed by the word transition or just transition. It is certainly difficult to find a compromise between two people, let alone between 200 countries, and that is why these seemingly “banal” things and discussions are necessary. Because in order to make any decision, preferably good and valid for the whole world, someone has to sit down and think. And so much so that he thinks that every paragraph, every word, every comma in a decision is combed through in order to determine the exact and unambiguous meaning of every sentence and so that no paragraph is left incomplete. After attending dozens of negotiation sessions at this 29th COP, we can tell you that most of these negotiations consist of just such “banal” but much-needed things.

And what exactly does that look like? So by, first, the delegations of the countries gather in one room and sit at the tables that are placed at right angles; in the center of that rectangle there are large monitors showing the working version of the text of a decision that is being negotiated. Then the delegations together go through every word and sentence in that text and give suggestions on what to remove, what to supplement, what to change. So, if everyone agrees, then it is done immediately, and if some disagree, then it is put in parentheses, and we continue until a general compromise is reached. The debating countries can represent themselves and participate in the negotiations individually, but usually several countries are grouped into groups represented by one country each, a representative of that group (so we have a group of 77 countries and China, then the African group, the Arab group of countries, the group of least developed countries etc.).

We will best illustrate it to you on the example of negotiations on national adaptation plans, and on the initial ones we attended. During these negotiations, the issue of the “qualification” of progress, as well as the word transition, which we mentioned at the beginning of the text, was raised. Namely, according to the decisions resulting from the Paris Agreement, it was stated that all countries should adopt national adaptation plans for climate change by 2025, above all the most vulnerable, which are developing countries. Thus, at these negotiations, among other things, the report on the progress so far in that field was adopted, so we went into the fine details of this report. On that occasion, the report raised the question of whether developing countries have achieved “limited” progress, as it says in the text, or only progress in adopting adaptation plans (around 40 countries have adopted plans out of over 130 of them). Western countries have questioned whether “limited” should be thrown out, because progress is progress and there is no need to qualify it. After that, other countries came forward with the desire that the adjective “limited” should remain, because it is necessary to emphasize in some way how much and what kind of progress has been made. “Limited” was left in the bracket though and the discussion continued. After that, Western countries came back again with the desire to modify the sentence that says that financial support for developing countries should be increased for the sake of the transition period from the adoption of the plan to its implementation. Namely, they believe that there is no “transitional period” in this field and that the word “transitional” should be removed. Because, as they explain, as soon as the plan is made, everything after that is implementation. However, Egypt responded with a counterargument that a transition period still exists for them, and that qualification should remain. Because when they finish the plan, the developing countries do not start immediately to implement it, but first to secure financial resources for it, so that period is precisely called transitional for them.

As developing countries make a transition, we will stop here and make a transition to the next segment of the text. This was the impression and the essence of the negotiations themselves, which we saw at the beginning and wanted to convey to you, while in the following we will convey to you impressions from many more negotiations that we attended.

Compromises are difficult…

At the COP in Baku, we learned a lot about the challenges and possibilities of reaching a compromise. Sometimes it’s easy, and sometimes it’s incredibly difficult, as we experienced firsthand during the negotiations we attended. Two examples were particularly interesting – one that illustrated sharp confrontations, and the other the surprising speed of reaching an agreement.

Before the start of the negotiations on the national adaptation plans, we found the end of the second meeting in the hall, which was related to the least developed countries. The situation became unusual when a majority vote decided to completely delete a paragraph proposed by Saudi Arabia from the decision. This drastic move caused laughter among observers, as the deletion of that paragraph effectively nullified all of Saudi Arabia’s work on the subject. Although the Saudi delegation resented it, for the sake of compromise they accepted this decision and continued participating in the negotiations. This moment reminded us of the dynamics of the COP, where compromise is sometimes ruthless, but also necessary.

After this meeting, negotiations on national adaptation plans began. Instead of the expected intensive discussion, the chairman immediately at the beginning conveyed the decision of the “Subsidiary Body for Implementation” (SBI). The decision suggested that the negotiations be suspended and resumed only in June 2025 at the next meeting of that body. This proposal caused the indignation of many countries, especially the representatives of Fiji before the Group of 77 and China. Fiji stressed that it was unacceptable to delay the negotiations, as this could undermine the progress made so far. Suddenly, Fiji requested a break for consultations, which the chairman granted with a smile.

The break resulted in an interesting scene: about 77 representatives get up and leave the hall to discuss in the corridor (we didn’t count them, but from the name of the group we believe there were at least that many 😊). After a long time, they returned and negotiations continued, but not for long. After maybe ten minutes since the negotiations continued, the representative of Fiji called again and with a smile again asked for a break for consultations, which the chairman approved with an even louder laugh. After even longer consultations, the representatives returned to the hall and the negotiations continued. Fiji pointed out, for some reason, that they may not have understood each other, but that they are still in favor of continuing negotiations at this COP. After expressing support from other delegations, the decision was abruptly changed, and negotiations continued. Obviously, the influence to change this decision was achieved during the “pause”, because it was not visible during the negotiations themselves. We do not know whether the “phones” to other countries or members of the implementation body (SBI) were working during the “pause”, but we do know that the decision was changed and that the negotiations continued, which all illustrates how informal talks often play an important role in formal negotiations. It was said that the countries will be informed about the new date and time of the negotiations.

Another significant part of the COP was the discussion on Article 6 paragraph 4 of the Paris Agreement, which refers to the market for carbon dioxide emissions. This mechanism allows countries to cooperate in reducing emissions through the exchange of “carbon credits”. Countries that invest in reducing emissions in their own or another country can count those reductions as their contribution to the goals of national energy and climate plans, or sell them to other countries to count those reductions as their own. Although the discussion was mostly of a technical nature, the importance of this mechanism for the global fight against climate change is great and it is considered one of the main ways to secure the financial resources that are the main topic of discussion at this COP.

Particularly interesting were the negotiations on guidelines for the development of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). These documents are the core of the Paris Agreement and define national plans to reduce emissions. The guidelines should help countries in making the best possible plans. Although the deadline for the preparation of the initial NDCs was until 2020, some countries did not fulfill this obligation, so the new deadline was moved to 2025. It was also agreed that these documents should be revised, with the aim of improvement, every 5 years, which is expected next year by most of the countries that adopted these documents on time. Despite this, there have been doubts about whether work on the guidelines is needed now, as they could only be completed after all countries have submitted their new plans and improved existing ones.

Opinions were divided: Korea considered that work on this document is currently unnecessary, as it will be created when all countries have completed their work and will only represent a missed opportunity, while the EU emphasized its importance for researchers, who can use this database all over the world. and contribute to its future application. China suggested defining the guidelines as a “living document” that can continue to grow and develop. All agreed that these guidelines should be completed by 2027, so that they would be applicable to the new generation of NDCs in 2030. It was then agreed that at the next session, three options will be presented regarding the time to continue working on this document, among which the countries will choose one.

All these discussions show that negotiations at the COP are complex and often lengthy processes. Nevertheless, they represent a key platform for achieving global climate goals through compromises and cooperation.

Compromises, whatever they are…

As time goes on, the negotiations at the COP gradually progress, either through reaching compromises, final agreements or steps closer to them. The impressions we bring from the meetings, although limited to those open to observers, provide insight into the complexity and dynamics of these important global discussions.

One of the significant events was the signing of the declaration on the joint cooperation of the Caspian states in the fight against the dramatic drop in the level of the Caspian Sea. Although this agreement was not part of the official COP negotiations, it was nevertheless reached on its margins and is worth mentioning. It was signed between Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia and Turkmenistan, with the support of the United Nations Environment Programme, and is a true example of how common interests can be placed above current political disputes. Since 2006, the level of the Caspian Sea has been continuously falling, which represents the longest period of decline in history, with a record loss of 30 centimeters in the last year alone. This declaration calls for experts to come together to develop solutions to this growing environmental problem, showing how cooperation can be key in meeting common challenges.

Negotiations on Article 6 paragraph 4 of the Paris Agreement continued in a familiar technical tone, with a focus on detailed aspects of market mechanisms for reducing carbon dioxide emissions. From the final proposal of the decision, we see that an agreement has been reached on the establishment of a body that will oversee the implementation of these mechanisms, a registry for monitoring emissions transactions and rules for reporting and authorizing “credits” for emissions. Frameworks for financing adaptation have also been determined, with the exception of the poorest countries from these obligations, if they so wish. It was also expressed the hope that when funds of 3.1 million dollars were not delivered in 2024 for the implementation of this mechanism, that they will manage to be secured in 2025.

When it comes to negotiations related to the creation of guidelines for the development of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), countries were offered three options to continue negotiations on this topic: to continue in 2025, 2026 or 2027. In a closed meeting the following day, which we could not we follow, a decision has been made about the time of continuation. However, as no official decision has been announced yet, the results remain unknown. This shows the importance of careful planning and establishing clear timelines for processes to run efficiently.

The negotiations on national adaptation plans, one of the last negotiations we attended, continued in a somewhat calmer tone after a stormy meeting, which attracted considerable attention from observers. Although the work at first seemed like a “boring” analysis of wording and putting parts of the text in parentheses, it later took on a little more vigor. Namely, it was stated that there is no time at this COP to complete the negotiations and create the final version of this document. The chairman, America, the European Union, Canada and New Zealand proposed that then as the final working version of the text be sent the one that was done until that “turbulent” meeting, and that everything that was done after that be sent as an informal note. With the addition that, if some countries were strongly against it, they would be ready for everything that was done after that meeting to be included in the final version of the document as well, but to be put in parentheses to make a difference between before and after that. We did not know what the weight of the “informal note” was, but from the expressions of opposition to it from the group of 77 countries and China, India and the northern part of South America, we understood that the “informal note” could probably be rejected very easily, which could mean that everything they did after that “turbulent” meeting, for which they fought, could very easily be thrown into the water, which would nullify all their work. It said a short session, closed to observers, would be organized where countries would decide whether to go with or without an “informal note”. From the official document, we saw that a decision was made to include the parts created after the “turbulent” meeting in the working version of the document, but in brackets, to indicate that these parts are temporary. In this way, both parties were satisfied — one that insisted on preserving the previously reached agreement and the other that wanted the later work to be recognized as part of the process.

This approach to compromise reflects the essence of the COP: even in an atmosphere of chaos and disagreement, it is possible to reach a common solution. We are deeply impressed by the dedication of the participants to the smallest details. And we’ve seen that patience, persistence and attention to detail are key to success.

The negotiators used to, without hesitation, ask additional questions and ask for clarifications, often more than once, to make sure that there is no room for misinterpretation, which is one of the most memorable moments for us, and also a demonstration of how important it is to clarify every detail, even when it seems that everything is already clear. This process reminds us how important it is to be thorough and patient when dealing with complex issues. It’s a lesson we often forget, but one that was evident here at every turn.

We leave this COP inspired by examples of cooperation and compromise. Although climate change remains one of the biggest challenges of our time, these negotiations are proof that joint effort is the best way to a sustainable future. With more knowledge and motivation, we continue our work, believing that even small steps can bring big changes in the search for a better tomorrow.